Prospecting with a technical edge

Maximize Your Gold-Finding Potential

Story and photos

by Karla Tipton

January 2003

From Rock & Gem magazine, reprinted with permission, copyright Miller Magazines Inc.

The dryness of the desert air burned our lungs. The temperature was rising in Lucerne Valley, California, as our Toyota 4X4 truck rattled over the sandy dirt road toward the Camp Rock gold placer area. We had been driving along the same dirt road for 20 minutes, and nothing but scrub brush and some rocky hillocks could be seen for miles in any direction. How could we be certain of our location? Was it possible we had missed our turnoff? Was there a chance we weren't anywhere close to the destination we had set as our goal?

Not a doubt entered our minds. We were on target, and we knew it. We had only to look at the pointer on our GPS screen to know the mining area was exactly 0.56 mile away.

A new technique for pinpointing the locations of lost sites is now available to the small prospector and many don't even know about it. The technique makes use of the Global Positioning System (GPS) and a little old-fashioned book research. Together, these two things create an enormous resource for discovering hard to-find mines, old ghost towns, and other locations lost in the remote past.

In fact, it may turn out that the GPS will become to the small prospector what electro-optics and remote sensing has become to large mining companies a method for finding the goods quickly and cheaply.

The GPS consists of 24 satellites in orbit. With

appropriate receiving equipment, the system can be used to determine

geographical coordinates such as longitude and latitude. In addition to

mapping, surveying and monitoring, the GPS is an excellent navigation

tool. And while GPS is an acronym used to refer to the system, it also

commonly refers to the small handheld units that make use of this

system.

The GPS consists of 24 satellites in orbit. With

appropriate receiving equipment, the system can be used to determine

geographical coordinates such as longitude and latitude. In addition to

mapping, surveying and monitoring, the GPS is an excellent navigation

tool. And while GPS is an acronym used to refer to the system, it also

commonly refers to the small handheld units that make use of this

system.

Hikers have been using these handheld devices for years to get around in the wilderness. Now the prices have dropped so dramatically that a variety of GPS units can be purchased for less than $100. Many high-end GPS units even have road and topographical maps built in.

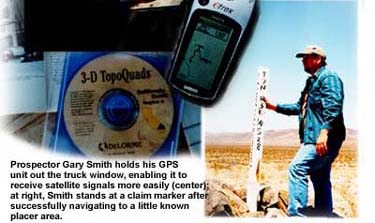

Our Garmin eTrex Vista cost about $350. In the past year, recreational prospector Gary Smith has used this little 5.3-ounce unit to discover a variety of "lost" places. He has found more new locations to work in the past year than he had in his past decade of prospecting.

"The GPS is now the No. 1 tool that I use," said Smith, who was recently featured in a New York Times "Circuits" article ("Gold Prospectors Go Digital," March 14, 2002) for his application of cutting edge technology to the age-old discipline of prospecting. Smith primarily hunts for gold in the rich El Paso Mountains near Randsburg, California.

Like most hobbyists, he dreams about doing recreational prospecting full-time, but in reality he can't afford to give up his day job, so precious weekend hours are about all the time he has. "Before I got the GPS, it would take me most of the day to find what I thought was a good area to work, and I still couldn't be sure that I had really found it," Smith says. "Now I can sit at night, days prior to a trip, plan it all out, and program it into the GPS. I maximize my time out there, and know I'm actually looking in the right place. And I get some quality time to work in the area.

"I do all the research I can," he added. "I go through the books, use the Internet, and look up locations on the topographical maps that are available on CD."

The best sources are government publications dating from the 1890s and the 1930s, especially the latter. "During the Depression, a lot of people went back to hunting gold, trying to make a living," said Smith. "There's a lot of information from that time period."

Libraries are excellent repositories for these resources. With the advent of the Internet, an entire library's catalog is available for searching online. By using the interlibrary loan service offered at almost every library in the country, you can check out the books from remote libraries and pay only the cost of mailing the book to your local branch.

In addition, some older publications are still available in the inventories of such agencies as the U.S. Geological Survey. You can peruse the index of texts online and download an order form if you find one you want to buy. Rare publications can also be found on eBay and other auction Web sites. Many bookstores that sell used books also make their inventories available for searching online. On his Web site, www.goldledge.com, Smith sells CD-ROM copies of these public domain publications, saved electronically in the Adobe Acrobat format and fully searchable by key word.

Smith found reference to the Camp Rock placer area in an old mining publication published in 1953 by the State of California Department of Natural Resources on the mines and mineral deposits of San Bernardino. Hard to find, but relatively recent in the timeline of California mining, this publication sold on eBay for a very affordable $30 or so. Included in this report are descriptions of mining operations and geological features of this 20,000-square-mile area of the Southern California Mojave desertincluding range and township coordinates. Range and township information for historical mining areas is the richest ore of all for those in search of lost gold.

The location of the Camp Rock placer area is cited as being located at Township 7 North, Range 3 East, Section 28, which would most likely be abbreviated as T7N, R3E, S28. Knowing the meridian is also important; in this case, it is the San Bernardino Meridian.

For those who use topographical maps, township/range/section information should be familiar. How this mapping system came into use may be more of a mystery, however. The range and township coordinate system was developed to map the area of the United States west of the Ohio River, beginning in 1784, as new territories were settled. In each area to be surveyed, a reference point was established from astronomical observations upon which the survey would be based. From the reference point, a true north-south line was projected to the limits of the area to be surveyed. Also from the reference point, an east-west line, following a true parallel of latitude, was projected to the limits of the area. Townships, as close to six miles square as possible, were formed parallel to the reference lines. The townships were further divided into one-mile-square sections. A column of townships extending north-south was called a range and a row of townships running east-west was called a tier (a term eventually replaced by the word "township"). Sections can be quartered repeatedly to define a position. It is these township/range designations that appear as numbers and letters on the edges of topographical maps. Original Spanish land grants were excluded from the range and township survey.

Before the township and range information can be used with your GPS, it needs to be converted to longitude and latitude. A good converter, available online from Montana State University (www.esg.montana.edu/gl/trs-data.html), provides the longitude/latitude equivalent of the township and range coordinates, which in this case is 34.66694, 116.67138 (also read as 34°, 40', 1.0" N; 116°, 40', 17.0" W).

The converter, a computer program written by Marty Wefald, provides nearby "named" places, and a Web link to that position on the Microsoft TerraServer (www.terraserver.microsoft.com). The satellite images of the United States available on the TerraServer can be zoomed in to amazing detail, revealing recognizable structures and rock formations.

Range and township information can also be entered into mapping software, such as Topo USA 4.0 or 3-D Topo Quads (by state), available on CD-ROM from Delorme (www.delorme.com). This provides the longitude and latitude coordinates, as well as a printable map you can use to get to your targeted location. With additional accessory cables to interface with your PC and sufficient built-in memory in the GPS, the map data can be downloaded right into your handheld unit.

The Topo USA software may be considered a bit pricey by some standards (about $100), so there is a cheaper way. Once the longitude and latitude coordinates have been determined, these can be programmed directly into the GPS as a destination point, called a "waypoint" in GPS terminology. By studying a more traditional paper topographical map, you can then calculate additional township/range coordinates along the route you plan to take, and enter these into the GPS as additional "waypoints," creating a kind of portable electronic breadcrumb trail. All that's left is to turn on the GPS's navigation function and switch to the device's map screen, hop in your 4X4, and start driving.

As you travel, a line capped with an arrow is drawn on the GPS liquid-crystal display screen indicating how closely you are following the route mapped by your programmed waypoints. You can expect to veer off slightly, as roads are not always mapped with precision on topo maps. Dirt roads can also change course somewhat over the years as they are washed out and remade. But if you turn the wrong direction entirely, you'll know immediately, because the arrow will be traveling in the opposite direction from your destination. The tracking arrow and your final waypoint will eventually coincide as you reach your destination.

GPS accuracy is based on the relationship of the device to at least three satellites, known as triangulation. To triangulate, a GPS receiver measures distance using the travel time of radio signals. In 2000, restrictions affecting the accuracy of GPS consumer models were lifted by the Defense Department, which operates the system. As a result, even the lower-end GPS units have accuracy to 30 feet under the best operating conditions. In addition, the closer you are to the equator, the more likely your GPS will be able to receive signals from Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS). A ground- and space-based system designed for airplane guidance, WAAS signals improve accuracy to within 15 feet. So far, there are only a few deployed WAAS satellites that are in a fixed orbit around the equator and appear close to the horizon in North America. Ground-based GPS units have difficulty picking up the signals in terrain containing trees or other tall obstructions.

Since we were in the high desert of Southern California with virtually no obstructions, the WAAS system enhanced the accuracy of our GPS. As we closed in on the Camp Rock placer area, the dirt road ended at a group of craggy granite hills. Workings of old mining operations dotted the landscape. Throughout the general area, there were historic structures and equipment, and several tunnels. A claim marker denoting the location confirmed that we had indeed arrived at our destination. Without fuss and without wasting time on aimless wandering over unknown trails, we had reached our goal.

Some earlier research on the Bureau of Land Management Web site (www.blm.gov/lr2000) had informed us that while one corner of the section was actively claimed up, there were many nearby areas no longer under legal claim and available for us to work. Now, the many hours that remained in the day could be used for the real work of finding gold.

Entire cultures are springing up around the use of the GPS. Groups of techno-literate genealogists now use it to search for lost cemeteries and family homesteads. And there's a group of high-tech treasure hunters who do "geocaching," a new pastime that usually includes four-wheeling, hiking and searching for a "cache" of modern-day souvenirs left by other geocachers.

The practical application of new technologies to our outdoor pastimes

can sometimes be difficult to discern. And perhaps something of the

romance of treasure hunting is lost when we give up our magnetic compass

and "X-marks-the-spot" paper map. However, there's no denying that the

use of the GPS in conjunction with traditional researching methods might

just lead you to the real "pay dirt."